In the Fall of 2010, I was approached after class by Josh Spann, one of my Au.D. students at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences. In class, we had been talking here and there about various Apple and Android apps that might help us understand audiology instrumentation. In particular, we were playing with sound level meter and spectrum analyzer apps. Josh, being an Apple product buff, asked me if I would be interested in purchasing an iPad that had just recently come out; however, when he asked it was more like a challenge or dare. His exact words: “I’ll buy one if you do.” I agreed, though my only prior experience with Apple products was an iPod I received for Christmas in 2008.

In the Fall of 2010, I was approached after class by Josh Spann, one of my Au.D. students at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences. In class, we had been talking here and there about various Apple and Android apps that might help us understand audiology instrumentation. In particular, we were playing with sound level meter and spectrum analyzer apps. Josh, being an Apple product buff, asked me if I would be interested in purchasing an iPad that had just recently come out; however, when he asked it was more like a challenge or dare. His exact words: “I’ll buy one if you do.” I agreed, though my only prior experience with Apple products was an iPod I received for Christmas in 2008.

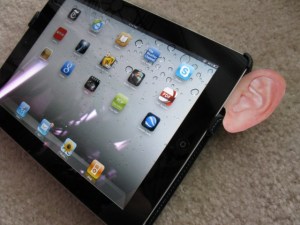

Our individual purchases led us both down an interesting path on dreaming up ways to incorporate the iPad (and other handheld touch-screen devices such as iPhone, iPod Touch, and Android smartphones) into the audiology clinic. It wasn’t long before we each discovered that a number of app developers were taking advantage of the Apple and Android platforms to create amplifiers that mimic hearing aids. By our last count (as of May 2012), there were 17! Earlier this year, Josh, Jason Johnson (another Au.D. student) and I downloaded 12 apps from the Apple Store and we collectively rated them and performed electroacoustic analyses (EAA) to see what their respective maximum OSPL90 levels were at the highest volume setting. Though the study and various permutations are still underway as part of Josh’s Au.D. Capstone Research project, I’m happy to share with you some of the information we wrote in a consumer article for the Hearing Health magazine (Atcherson et al., 2012) and presented in an invited Featured Session at the 2012 AudiologyNOW! convention in Boston (Atcherson & Spann, 2012). Our interest in the output of amplifier apps is not limited to the iPad, however. We are systematically evaluating some different Apple and Android products. For this blog, I’ve added for good measure three recently discovered Apple apps and two Android apps I found as a current Motorola Droid X user.

Our individual purchases led us both down an interesting path on dreaming up ways to incorporate the iPad (and other handheld touch-screen devices such as iPhone, iPod Touch, and Android smartphones) into the audiology clinic. It wasn’t long before we each discovered that a number of app developers were taking advantage of the Apple and Android platforms to create amplifiers that mimic hearing aids. By our last count (as of May 2012), there were 17! Earlier this year, Josh, Jason Johnson (another Au.D. student) and I downloaded 12 apps from the Apple Store and we collectively rated them and performed electroacoustic analyses (EAA) to see what their respective maximum OSPL90 levels were at the highest volume setting. Though the study and various permutations are still underway as part of Josh’s Au.D. Capstone Research project, I’m happy to share with you some of the information we wrote in a consumer article for the Hearing Health magazine (Atcherson et al., 2012) and presented in an invited Featured Session at the 2012 AudiologyNOW! convention in Boston (Atcherson & Spann, 2012). Our interest in the output of amplifier apps is not limited to the iPad, however. We are systematically evaluating some different Apple and Android products. For this blog, I’ve added for good measure three recently discovered Apple apps and two Android apps I found as a current Motorola Droid X user.

Table 1 (below) lists the 17 apps with the respective developers, version number, price, device, and measured maximum OSPL90. Thirteen of the apps appear to be marketed specifically as personal amplifiers (i.e., hearing aids). The other three, however, come under a different guise. The Microphone and Megaphone apps (Apple) are designed to be used as a public address amplifier by adding a pair of computer speakers and using the device’s built-in microphone. We substituted computer speakers with ear buds and turned the app into a hearing aid. The Super Hearing app (Android) is what appears to be a novelty for hearing conversations from a distance (like a spy device). The iStethoscope Pro app (Apple) is also a novelty and requires one to place the microphone of the iPhone/iPod on one’s bare chest, which is supposed to act like a crude version of a stethoscope bell and diaphragm chestpiece. Within the stethoscope app is a conversation mode reminiscent of a clever stethoscope trick I’ve heard used with patients with hearing loss by some healthcare providers. The clever trick is that they are placing the stethoscope eartips into their patients’ ears (hopefully after disinfecting them first, Dr. Bankaitis) and speaking directly into the chestpiece. Used in this way, the stethoscope acts like a personal amplifier for the patient.

Table 1 (below) lists the 17 apps with the respective developers, version number, price, device, and measured maximum OSPL90. Thirteen of the apps appear to be marketed specifically as personal amplifiers (i.e., hearing aids). The other three, however, come under a different guise. The Microphone and Megaphone apps (Apple) are designed to be used as a public address amplifier by adding a pair of computer speakers and using the device’s built-in microphone. We substituted computer speakers with ear buds and turned the app into a hearing aid. The Super Hearing app (Android) is what appears to be a novelty for hearing conversations from a distance (like a spy device). The iStethoscope Pro app (Apple) is also a novelty and requires one to place the microphone of the iPhone/iPod on one’s bare chest, which is supposed to act like a crude version of a stethoscope bell and diaphragm chestpiece. Within the stethoscope app is a conversation mode reminiscent of a clever stethoscope trick I’ve heard used with patients with hearing loss by some healthcare providers. The clever trick is that they are placing the stethoscope eartips into their patients’ ears (hopefully after disinfecting them first, Dr. Bankaitis) and speaking directly into the chestpiece. Used in this way, the stethoscope acts like a personal amplifier for the patient.

Though ANSI S3.22 (2003) has a number of different hearing aid performance test parameters, we focus here only on the maximum OSPL90 (or Maximum Power Output [MPO]). We used the Verifit system and 2-cc coupler for all testing as well as Apple stock earbuds for consistency across devices. Depending on the app, we had to use Apple earbuds with built-in remote microphone (e.g., iPhone version) or without (iPad or iPod version). In other words, some apps are designed to use the device’s built-in microphone,

Though ANSI S3.22 (2003) has a number of different hearing aid performance test parameters, we focus here only on the maximum OSPL90 (or Maximum Power Output [MPO]). We used the Verifit system and 2-cc coupler for all testing as well as Apple stock earbuds for consistency across devices. Depending on the app, we had to use Apple earbuds with built-in remote microphone (e.g., iPhone version) or without (iPad or iPod version). In other words, some apps are designed to use the device’s built-in microphone,  whereas others depend on earphones or headphones with built-in remote microphones (such as for cellphone use). Referring back to Table 1, it should be clear that 5 of the 17 apps have OSPL90 values in excess of 130 dB SPL. What’s a bit scary is that there is a rule by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA; 21 C.F.R. 801, 2011) that for any medical device (i.e., hearing aid) that exceeds 132 dB SPL, special care and fitting must be taken by the dispenser to avoid pain and further damage. We knew from listening to some of these apps that they had the potential to be very loud, but we did not know how loud. We are concerned that improper use could in fact cause permanent hearing damage.

whereas others depend on earphones or headphones with built-in remote microphones (such as for cellphone use). Referring back to Table 1, it should be clear that 5 of the 17 apps have OSPL90 values in excess of 130 dB SPL. What’s a bit scary is that there is a rule by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA; 21 C.F.R. 801, 2011) that for any medical device (i.e., hearing aid) that exceeds 132 dB SPL, special care and fitting must be taken by the dispenser to avoid pain and further damage. We knew from listening to some of these apps that they had the potential to be very loud, but we did not know how loud. We are concerned that improper use could in fact cause permanent hearing damage.

In addition to our taking OSPL90 measures, we made very general ratings for 12 of the items (average of 3 independent raters) in our Hearing Health article. Our favorites were EARs (Ear Machine), SoundAMP R (Ginger Labs), eHear (MEA Mobile), and Microphone (PocketLab) which we assigned at least 4 out of 5 stars. We based our general ratings on ease of use, little to no acoustic delays (echos), and overall sound quality. By our assessment, an overwhelming majority of amplifier apps out there on the market are just not very good. We would like to point out that the EARs app was developed by psychoacoustics researcher, Andrew Sabin, Ph.D., a graduate of Northwestern University’s Communication Sciences and Disorders program.

In addition to our taking OSPL90 measures, we made very general ratings for 12 of the items (average of 3 independent raters) in our Hearing Health article. Our favorites were EARs (Ear Machine), SoundAMP R (Ginger Labs), eHear (MEA Mobile), and Microphone (PocketLab) which we assigned at least 4 out of 5 stars. We based our general ratings on ease of use, little to no acoustic delays (echos), and overall sound quality. By our assessment, an overwhelming majority of amplifier apps out there on the market are just not very good. We would like to point out that the EARs app was developed by psychoacoustics researcher, Andrew Sabin, Ph.D., a graduate of Northwestern University’s Communication Sciences and Disorders program.

We are at an interesting crossroads in audiology in terms of the accessiblity of consumer-based apps that are accompanied with little to no regulation and little to no oversight by audiologists or other hearing professionals. Current amplifier apps on the market are, at best, novelty items and care should be used. We applaud several of the app developers for posting warnings with their apps, but not all do, and they probably should. Audiologists should take a cautious approach when consulting with patients about these apps. With proper instruction or use, some of these apps can be used safely and effectively in lieu of actual hearing aids with some benefit for some patients (see e.g., Eisenberg, 2012).

We are at an interesting crossroads in audiology in terms of the accessiblity of consumer-based apps that are accompanied with little to no regulation and little to no oversight by audiologists or other hearing professionals. Current amplifier apps on the market are, at best, novelty items and care should be used. We applaud several of the app developers for posting warnings with their apps, but not all do, and they probably should. Audiologists should take a cautious approach when consulting with patients about these apps. With proper instruction or use, some of these apps can be used safely and effectively in lieu of actual hearing aids with some benefit for some patients (see e.g., Eisenberg, 2012).

Samuel R. Atcherson, Ph.D. is an assistant professor in the Department of Audiology and Speech Pathology at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock in consortium with the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences. He received his bachelors and masters degrees from the University of Georgia (1997 and 2000) and his doctorate from the University of Memphis(2006). Since 1997, Sam has given over 90 presentations to a variety of audiences on topics related to hearing assistive technology, mainstream hearing loss, classroom acoustics, age-related hearing, electrophysiology, auditory processing disorders, and health literacy. He is author of over 50 non-peer- and peer-reviewed publications, four book chapters, and two books: Auditory Electrophysiology: A Clinical Guide and Demystifying Hearing Assistance Technology: A Guide for Service Providers and Consumers. Sam is a long-time affiliate and Past President of the Association of Medical Professionals with Hearing Losses, a co-founder of the Association of Audiologists with Hearing Loss, and a proud board member of the Arkansas Hands and Voices chapter.

Samuel R. Atcherson, Ph.D. is an assistant professor in the Department of Audiology and Speech Pathology at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock in consortium with the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences. He received his bachelors and masters degrees from the University of Georgia (1997 and 2000) and his doctorate from the University of Memphis(2006). Since 1997, Sam has given over 90 presentations to a variety of audiences on topics related to hearing assistive technology, mainstream hearing loss, classroom acoustics, age-related hearing, electrophysiology, auditory processing disorders, and health literacy. He is author of over 50 non-peer- and peer-reviewed publications, four book chapters, and two books: Auditory Electrophysiology: A Clinical Guide and Demystifying Hearing Assistance Technology: A Guide for Service Providers and Consumers. Sam is a long-time affiliate and Past President of the Association of Medical Professionals with Hearing Losses, a co-founder of the Association of Audiologists with Hearing Loss, and a proud board member of the Arkansas Hands and Voices chapter.

References

Atcherson, S.R., Spann, M.J., & Johnson, J. (2012). 12 apps to help you hear better. Hearing Health, 28(2), 20-22.

Atcherson, S.R. & Spann, M.J. (2012, April). iAudiology: integrating tablets into audiology practice. Presentation at the 2012 AudiologyNOW! convention, Boston, MA.

Eisenberg, A. (2012, May 5). For hard of hearing, clarity out of the din. New York Times: Business: Technology. URL: http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/06/technology/audio-devices-give-new-options-to-those-hard-of-hearing.html

Hearing Devices, Professional and Patient Labeling, 21 C.F.R. § 801 (2011).

Klinger, M. & Lesner, S. (2012, March 28). Multitasking for patients 101: how to use mobile devices as hearing assistance technology. Presentation at the 2012 AudiologyNOW! convention, Boston, MA.

Like this:

Like Loading...

Twenty years ago, a little company called Oaktree Products was founded in 1992 by Robert J. Kemp in the basement of his Chesterfield, MO home. As Product Manager in the Marketing Department at Marion Laboratories, Bob was responsible for overseeing Debrox, a cerumen softening product produced and distributed by his former employer. Through his various travels, his path crossed with none other than Ross Roeser. When asked what he did for a living, Dr. Roeser identified himself as an audiologist; as they were talking, the evolution of the profession’s scope of practice to include cerumen management was mentioned and, you guessed it, the rest is history.

Twenty years ago, a little company called Oaktree Products was founded in 1992 by Robert J. Kemp in the basement of his Chesterfield, MO home. As Product Manager in the Marketing Department at Marion Laboratories, Bob was responsible for overseeing Debrox, a cerumen softening product produced and distributed by his former employer. Through his various travels, his path crossed with none other than Ross Roeser. When asked what he did for a living, Dr. Roeser identified himself as an audiologist; as they were talking, the evolution of the profession’s scope of practice to include cerumen management was mentioned and, you guessed it, the rest is history. The name Oaktree Products was actually code for a special project brainstorm by Bob and Ross that involved audiologists visiting nursing homes to perform otoscopy and identify seniors with impactions who could have hearing improved via cerumen removal. The special project was referred to as Optimizing Auditory Kommunication Through Routine Ear Examinations. While the special project never really took off, the name Oaktree stuck and, hence, the origin of Oaktree Products. Given his background and interactions with Dr. Roeser, Bob introduced the very first product offered by Oaktree Products: Audiologist’s Choice® Earwax Removal Drops.

The name Oaktree Products was actually code for a special project brainstorm by Bob and Ross that involved audiologists visiting nursing homes to perform otoscopy and identify seniors with impactions who could have hearing improved via cerumen removal. The special project was referred to as Optimizing Auditory Kommunication Through Routine Ear Examinations. While the special project never really took off, the name Oaktree stuck and, hence, the origin of Oaktree Products. Given his background and interactions with Dr. Roeser, Bob introduced the very first product offered by Oaktree Products: Audiologist’s Choice® Earwax Removal Drops. The first employee that Bob hired was his wife Margy; prior to coming on board, Margy was managing three small children (Katie, Michael, and David) while selling homes via her real estate license that was earned specifically to put food on the table during the early years of the business. While all three of the children are now grown with college degrees, Bob and Margy have a new home of mouths to feed in the 19 full-time and three part-time people employed at Oaktree Products. As their dog, I can honestly say that Bob and Margy are the best owners in the world. Congratulations on twenty years!

The first employee that Bob hired was his wife Margy; prior to coming on board, Margy was managing three small children (Katie, Michael, and David) while selling homes via her real estate license that was earned specifically to put food on the table during the early years of the business. While all three of the children are now grown with college degrees, Bob and Margy have a new home of mouths to feed in the 19 full-time and three part-time people employed at Oaktree Products. As their dog, I can honestly say that Bob and Margy are the best owners in the world. Congratulations on twenty years! Sassy B. Kemp is the Director of Employee Satisfaction at Oaktree Products, Inc., a multi-line distributor of hearing healthcare products located in the greater Saint Louis area. Since 2005, her role at Oaktree Products involves making rounds every morning at the office to ensure employees are in a good mood and ready to provide the highest level of customer service. A King Charles Cavalier Spaniel, Sassy is the official greeter of visitors to Oaktree Products, wagging her tail and providing a warm welcome to guests coming to the office. When employees need a mental break, she gladly accompanies them on short walks outside around the company grounds to clear minds. In the afternoon she naps before going home.

Sassy B. Kemp is the Director of Employee Satisfaction at Oaktree Products, Inc., a multi-line distributor of hearing healthcare products located in the greater Saint Louis area. Since 2005, her role at Oaktree Products involves making rounds every morning at the office to ensure employees are in a good mood and ready to provide the highest level of customer service. A King Charles Cavalier Spaniel, Sassy is the official greeter of visitors to Oaktree Products, wagging her tail and providing a warm welcome to guests coming to the office. When employees need a mental break, she gladly accompanies them on short walks outside around the company grounds to clear minds. In the afternoon she naps before going home.